Fantastic global methods in Ruby and where to find them

Many languages allow defining methods globally, which makes them available everywhere. Ruby is not different: you can define a method on the “top–level” and it behave like a global one. However, everything in Ruby is class, which means that these methods should belong to something. In this post we will figure out how global methods really work in Ruby!

Run the irb and define the method like usual:

def foo = 42

If you try to call it—you’ll obviously get 42. What does it mean? It goes without saying that the method works and we can call it, but the interesting part is not about it. We know that Ruby is purely object–oriented language: everything is class or instance of the class.

All examples in this post can be run in IRB or copied to file and run using the

rubyinterpreter, the result would be the same

Let’s create a new class and try to call #foo from it:

class Example

def run_foo

foo

end

end

Example.new.run_foo # => 42

It works! Our method can be called even from the method in a different class. It behaves like a global method.

Wait, doesn’t it sound suspicious? We defined the method globally and we can call it but there is no global scope: it should be defined in some class. So where is it defined?

Ruby object model

This section is a brief recap of the Metaprogramming Ruby 2 by Paolo Perrotta and Crafting Interpreters by Robert Nystrom

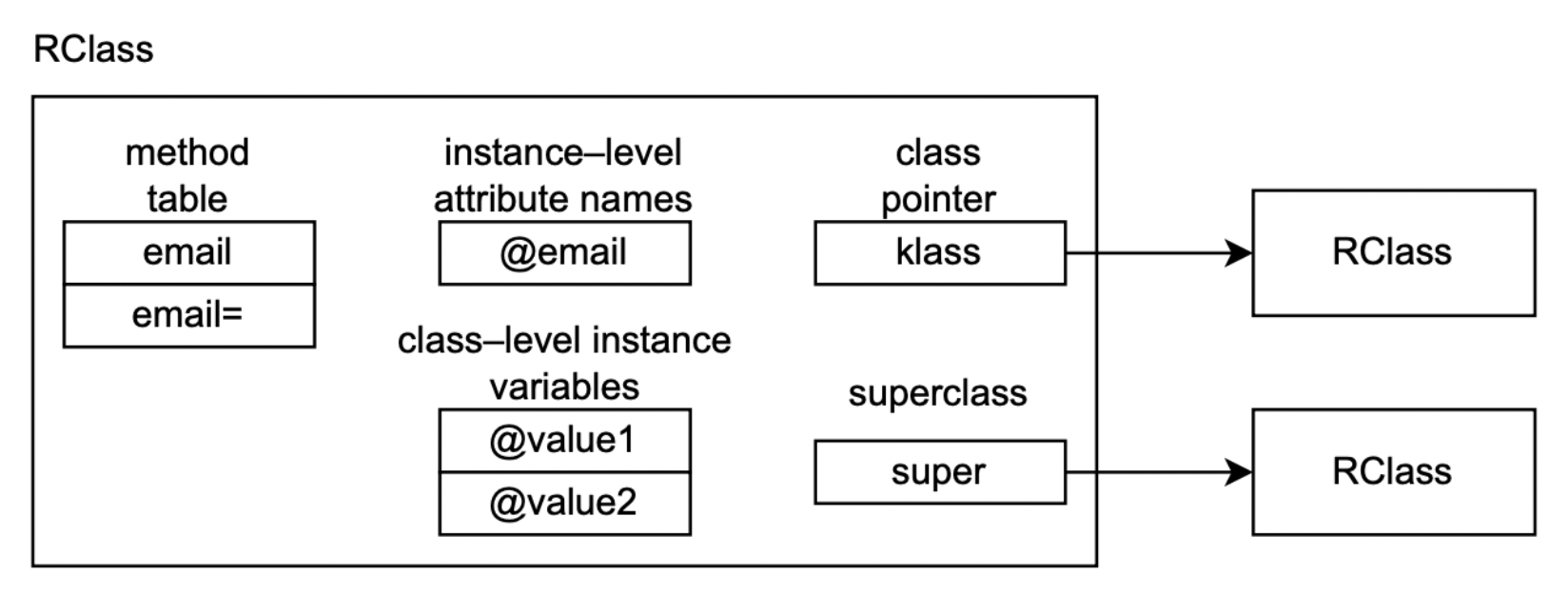

Every class in Ruby is the instance of the class called Class. In the Ruby VM it’s represented as a structure called RClass, which contains:

- a list of methods;

- a list of instance variable names;

- a list of class–level instance variables;

- a pointer to the class this class is instance of (as we know, it’s

Class); - a pointer to the superclass, which is a parent class for the current one.

According to the encapsulation principle of Object–Oriented Programming, data should be bound to the methods that operate on that data into a single unit. However, implementing it in the VM would require copying the byte code of methods to the each instance of the class. Since methods are shared, it makes sense to keep them in the single place, and Ruby keeps them in the instance of the Class (e.g., the byte code of #run_foo is hold in the Example).

Because of the metaprogramming features of Ruby we can access and modify contents of the class in the runtime. With this knowledge, let’s try to understand, where the code from the “top–level scope” is executed.

Examining the top–level scope

Let’s try to understand where we are when we write the code on the top–level scope outside of any class:

puts self #=> main

It did not help a lot: we learned only that we are inside the object that overrides the #to_s method. Let’s check our class:

puts self.class # => Object

Good, we’re inside some Object, which is a default base class for all classes. If we are inside the Object instance and there is a #foo method, we are supposed to be able to create a new instance and call the method:

Object.new.foo #=> private method `foo' called for #<Object:0x00000001402cec50>

Exception: we cannot call the method because it’s private! Let’s make sure that it’s correct:

private_methods.include? :foo #=> true

Does Object have a base class?

Object.superclass # => BasicObject

According to the docs, BasicObject is a base class for new object hierarchies, and it’s completely empty. Therefore, “top–level” methods won’t be available in your class if you inherit right from it:

BasicObject.new.foo # => undefined method `foo' for #<BasicObject:0x00000001058d5648> (NoMethodError)

Let’s summarize our explorations:

- when some method is defined on the top–level scope, it’s defined in the

Objectclass; - this method can be called from any other class, except ones inheriting from

BasicObject; - the defined method is private, so it cannot be called directly on the instance of the

Object.

Looks like that’s the answer! There is no global scope, we can access the method on the top level (because it’s defined here) or in other classes (because they inherit from Object), but this method is not visible from the outside because it’s private.

What about variables?

Let’s repeat the experiment, but instead of defining foo as a method we are going to make it variable:

foo = 42

class Example

def get_foo

foo

end

end

Example.new.get_foo # => undefined local variable or method `foo' for #<Example:0x0000000126ac0d38>

Exception again! The problem is that foo was not available inside the method, because it’s not local for the instance of the Example class.

Like before, let’s check how foo was defined.

instance_variables # => []

No instance variables! Maybe it’s local?

local_variables #=> [:foo, :_, :version, :str]

Correct! Our variable foo is defined locally for the top–level scope (or, more preciselu, for the instance of the Object we are executing our code) and that’s why it’s not available inside the instance of Example, which inherits from the Object.

How does it work?

When we run Ruby script using ruby or REPL using irb, Ruby creates a new workspace for us. By default it will use TOPLEVEL_BINDING for everything, but it’s possible to pass a different binding to the workspace constructor. Here is a source code that runs a new IRB session.